“You won’t find a guidebook anywhere to predict what Samuel’s course will be. He is going to chart his own path, and it will be like no one else’s.”

By Susan Simmons | June 24, 2011

Cellist Pablo Casals once said, “The child must know that he is a miracle, that since the beginning of the world there hasn’t been, and until the end of the world there will not be, another child like him.”

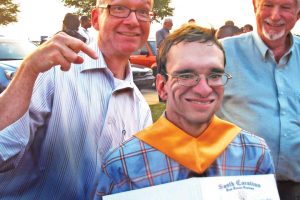

I tacked that quote on the bulletin board in my son’s nursery the week he was born, and remembered it June 1 as he crossed the Timmons Arena auditorium to receive his high school diploma, small and resolute in his yellow honors stole.

Two blinks and it was over; he was heading back to his seat. Such a short walk hardly seemed enough. He needed a Blue Angels formation flight. Phillip Sousa and cannon fire. I’m not sure even that would be enough, considering what it cost him to earn that piece of parchment from J.L. Mann.

Every diploma awarded that day is a celebration. But for Samuel, it was the trophy finish of an endurance race that began at midnight 21 years ago, as two Greenville Memorial Hospital residents fought to make a 2 lb., 10 oz. preemie breathe.

I still remember the weary pain in the neonatologist’s eyes the next morning when he told us our firstborn would not respond to the ventilator. The NICU staff had hand-bagged him all night. “Call your family,” he said. “I’m sorry, but I don’t expect him to survive the day.” He did, though, and the race was on.

Author Emily Pearl Kingsley once wrote that having a premature baby is like planning a fabulous vacation to Italy – only the plane lands in Holland.

“Holland?” you say to the stewardess. “What do you mean Holland? I signed up for Italy! I’m supposed to be in Italy. All my life I’ve dreamed of going to Italy.”

But there’s been a change in the flight plan, and in Holland you must stay. You must buy new guidebooks and learn a whole new language. You will meet people you never would have met.

Every NICU parent knows that essay. Samuel spent nine months in Memorial’s neonatal intensive care unit, so long that sometimes even now, if I happen to be at the intersection of Church Street and Augusta, I will drive on automatic pilot to Grove Road and find myself in the hospital parking lot. He stayed because he was so premature – he skipped the whole last trimester – and in the terrible Catch-22 of NICUs, his lungs were scarred by the ventilator he did finally tolerate and did save his life.

I am a worrier and a journalist, which made for trying times for the NICU staff. Every day I presented Samuel’s doctors with a fearful new syndrome I had discovered. “He doesn’t have that,” they would say, and I would find another what-if to worry about. Finally, one neonatologist told me he had an office full of books describing things Samuel did not have.

“I’ll give you full run if you want it. But you would do him far more good if you concentrate on what we know he does have,” he said. “You won’t find a guidebook anywhere to predict what Samuel’s course will be. He is going to chart his own path, and it will be like no one else’s.”

And so it has been. Samuel came home from the hospital with a tracheostomy and supplemental oxygen he was four years old before he outgrew. We had daily, 16-hour nursing care until he was three. Just breathing demanded so much energy he was 13 months old before he pushed up from a prone position, and almost five before he walked.

And he did it all with a mental toughness that shamed me for those weak and worried what-ifs, and made new people of his father and me.

It gave Scott the courage to quit work for three years of full-time childcare when the nurses finally left. (Samuel still had his trach, and I had the big company insurance policy.)

And it gave me the courage to get pregnant again, and give Samuel his brother Stephen, who was both light of his life and deepest comfort when he came home from the new trial that was school.

For we learned, when Samuel entered Sara Collins Elementary School, that he was a child of dramatic gaps. I wrote down a dream he described that kindergarten year: he had swallowed a tiger, he told us, and “when Daddy pulled it out of my mouth, it left the stripes behind.” But he could not open a school door, carry a lunch tray, or hold a pencil firmly enough to legibly write his name.

School from that day forward became for Samuel a maze of therapists, tutors, teachers and aides and for us, conferences with his Individualized Education Program team. As the labels piled up – other health impaired, specific learning disability, developmental delays – Scott and I fought to mainstream him in a regular classroom. His teachers argued for self-contained. He’s so frail, they warned; his deficits so profound. I knew they were right – but I also knew how his mind soared.

The decision was made by one of those people we would never have met outside of Holland: Penny Rogers, then the Greenville County Schools’ director of psychological services, who I am convinced can mind-meld with the children she tests.

“Samuel is bright. The tests show it,” she said at our last team meeting before first grade. “More important, he’s tough. He is frail and he is small, but he’s not a pet that needs protecting, he’s a boy – a bright, creative boy who will be a man someday, and it is our job to equip him to get there.”

Those words spurred and haunted us in the years to follow. Samuel managed to earn As and Bs in the regular classroom with accommodations and resource help. But he struggled with distractibility, executive function deficits and a daunting weakness in math. By sixth grade, he tested with a 12th-grade vocabulary and the physical dexterity of a first grader.

Those were hard years, and by high school we were close to despair. By this time, homework was devouring every evening hour and most weekends. The next four years looked insurmountable, mainly because Samuel did not know how to quit.

“You’ve been at this five hours,” his dad would say as he sobbed with fatigue over some incomprehensible math problem. “You can stop now and take a lower grade. It’s okay.” He would shake his head and bend over the paper again.

“You’ve been at this five hours,” his dad would say as he sobbed with fatigue over some incomprehensible math problem. “You can stop now and take a lower grade. It’s okay.” He would shake his head and bend over the paper again.

As a rising freshman, we faced a choice: should he keep struggling toward an academic diploma? Or was it time to dial back and seek an occupational one instead? He would learn life skills and career preparation, do some job shadowing. We asked Dr. Rogers to test him again and give us her advice. She did, and told us she was torn.

He was still a child with dramatic gaps, she said. “But he’s so bright. It’s a shame to deprive a student that bright of the chance to graduate.” How about this idea, she asked: stretch high school to six years. Reduce the classes he takes every year and add in resource periods to help him manage the workload. It would give him a chance to make it, if he could get past the exit exam, she said. She wasn’t worried about the English portion. But math – he “might not make it past the math.”

Samuel was fine with that, which told us how very heavy the load had been – and continued to be, even with the two extra years. For homework still devoured every evening hour and most weekends, and he still did not know how to quit. I lost count of the times we sent him to bed sobbing over some assignment undone by his perfectionism and snail’s pace. But the approach we’d chosen held: he made the J.L. Mann honor roll every reporting period the entire six years, thanks to the careful attention of his resource team, supportive teachers and a one-on-one aide who was tutor, advocate, confidante and friend.

But he couldn’t pass the exit exam. English, oh yes, first time out. But the math was a peak he could not climb. He took it fall and spring his second year, his third, his fourth. He and his aide drilled the basics again and again, his IEP team sought new accommodations, different proctors gave the test. He was so cata- tonic by his seventh try the next fall it surprised no one when he failed again.

“We have to try something new,” I told the team. “He cannot work this hard and leave next year with a certificate of attendance. He can’t.” They conferred with the district office. He spent the spring in a group review reserved for seniors who had one last shot at the exam. Conquering test anxiety was a major component. He said it helped.

Three weeks after school was out last June, we were crossing Sunset Boulevard atDisney’s Hollywood Studios when my cell phone rang. The guidance counselor’s voice almost deafened me when she shrieked, “He passed! He passed! I couldn’t wait until August to tell you he passed!” Soon I was shrieking, and then all four of us were dancing on Sunset Boulevard. Samuel was going to graduate from J.L. Mann.

“Holland is slower-paced than Italy, less flashy than Italy,” Emily Pearl Kingsley wrote. “But after you’ve been there awhile and catch your breath, you notice that Holland has windmills. Holland has tulips. Holland even has Rembrandts.”

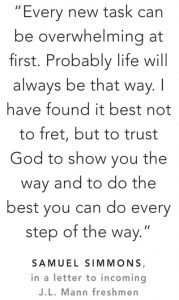

For a senior English project, Samuel’s class worked all year on a memory book detailing their journey through public school. The last assignment was a letter of advice to incoming freshmen. Samuel wrote:

“Every new task can be overwhelming at first. Probably life will always be that way. I have found it best not to fret, but to trust God to show you the way and to do the best you can do every step of the way.”

If he could change one thing, he wrote in an epilogue, it would be not to have been born early. “I wish I were taller, slightly larger perhaps, more athletic and more socially adept. (But) my practical side also figures that God felt these events needed to happen the way they did. They have certainly helped make me who I am today.”

Yes, Holland is tulips, and Rembrandts. Most of all, Holland is blessing.